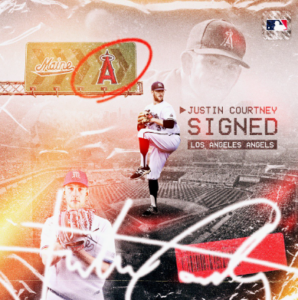

Justin courtney

interview by todd starowitz

In this installment of “My Baseball Journey,” NPA introduces Justin Courtney. A Bangor, Maine, and University of Maine product, the Justin reached Triple-A with the New York Mets organization in 2023.

Justin finished the 2023 as a pitcher for the Long Island Ducks of the independent Atlantic League, where he played on a roster that included more than a dozen former MLB players. Justin, who is also a certified NPA instructor, is currently a free agent.

Promising Career and injury

Justin, there aren’t many professional pitchers from Maine. Can you tell us about your career at the University of Maine?: “The first half of my sophomore season had been so good, and I got a Cape League contract with Chatham. I was like, here we go, I’m going to be a draft pick. But then my shoulder started acting up, and it hurt in the front and the back. The back side of my right shoulder was killing me, and I didn’t know why. I couldn’t figure it out, but I didn’t have any arm care program at this point in my career. We’d maybe do a little workout in the gym after a game. Nobody had a structured plan for us. I went in for a few different MRIs, and they told me I had a slap tear and that I’d have to do PT over the summer and not go to the Cape. I tried to return at the end of my college season for one or two appearances, but it wasn’t good. I didn’t want to go to the Cape with a bad shoulder. I spent that whole summer rehabbing my shoulder. Looking back on it now, it’s Tom’s theory about reciprocal inhibition, and the front of my shoulder was too strong for the back. When I got TJ (Tommy John surgery) two years later, it was probably the cascading effect. My shoulder was so weak that my elbow took many of the hits.

In April 2018, I started researching surgery. Maine had a good insurance policy that said I could go to any doctor in America because I got injured on the field, except for David Altchek in New York, the Mets team doctor, who didn’t take any insurance. Most surgeons had significant wait times, but Dr. Lyle Cain in Birmingham, Alabama, the team doctor for the Alabama football team, was only a twelve-day wait. Based on my research, he was the No. 2 to Dr. James Andrews, the gold standard.

Dr. Cain was a nice Southern gentleman trying to figure out what was wrong with my arm. I kept telling him my elbow didn’t hurt and only my forearm was painful. He told me it was torn within five seconds of touching my arm. He did the same test they had performed in Maine. He yanked on my arm, and I nearly screamed. He said, ‘It’s completely gone, isn’t it?’ I told him it felt like he would tear my arm off. He asked if anyone had pulled on my arm halfway close to what he did; I told him no. Everyone in Maine was trying not to break me because Maine doesn’t see many 95-mile-per-hour arms. They were so gentle. But when Dr. Cain yanked my arm, there was no doubt it was fully torn.

Andrews Sports Medicine resides in a wing of Ascension St. Vincent’s Hospital in Birmingham. I received all the plans for an accelerated rehab because I needed to return to a game in about a year. I returned to game action eleven months to the day following surgery. It was a rapid rehab for Tommy John. In my first game back, Dr. Cain came to Tuscaloosa after a full day of surgery to watch me pitch against the Crimson Tide. I gave up seven runs in four innings. But I was back in the game. Bama hitters figured out I was only throwing fastballs at that point, which didn’t end up well for me. I threw 79 pitches, which was too many. Dr. Cain waited until the game finished and walked to the bullpen to find me. I couldn’t have been more impressed. I still have his number, and I texted him when I signed with the Angels.

Following the 2019 season, forty rounds came and went in the MLB Draft, and I didn’t even receive a call. When I look back on it now, I’m glad I didn’t get drafted, but at the time, it was rough. My elbow wasn’t right; nobody selected me, and my college career ended. I used the 2019 summer to get healthy. In my eleven months of rehab, I saw Derek Loupin five days a week and my trainer at the University of Maine on the weekends. It was nonstop.

How did you go about trying to secure a professional contract?: That summer, I was trying anything to get signed. My dad, Jeff, drove me to Philadelphia for an open tryout with the Phillies at the Urban Youth Academy across from Citizens Bank Field. I threw 93 in a bullpen, and the regional scouting supervisor immediately wanted to know my story and why I was there and not playing professionally somewhere. They told me they’d get in touch. Two weeks later, I did the same in Cincinnati with the Reds. The Reds had pitchers face live hitters if they advanced past the bullpen round. I was throwing in the low nineties, and they brought me back to face hitters, and I struck out three hitters in twelve pitches. They told me I needed to go to independent ball to ensure I was healthy. I was frustrated because I dominated the three players I faced, but it still wasn’t enough.

Every year, Maine hosts a scout day for any interested professional organizations. In 2018, Jeremy Peña was playing for Maine. He subsequently went on to win the World Series MVP with the Houston Astros in 2022. We had scouts from all thirty teams, several assistant general managers, some regional scouting supervisors, and crosscheckers. Nearly fifty evaluators had come to see Peña, and I couldn’t throw because of my injury. Our manager was considerate enough to let me throw at their scout day in 2019. Peña wasn’t there, and the Padres, Blue Jays, and Yankees were the only teams that sent scouts. I threw 92 to 94, which was the best I’d thrown. I convinced myself one of these three teams would sign me. The Yankees regional scout at the time, Matt Hyde, had a relationship with one of our assistant coaches, and he called me after the scout day. He said, ‘Look, this is the best I’ve ever seen you throw. I’ve seen you since you were in high school, but I can only sign you if you throw 95. The Yankees want to see guys throwing 95, and that’s what it will take for me to sign a 22-year-old righthanded pitcher who has finished college.’ I was thankful for the feedback and Matt’s honesty.

working with the NPA

How did you first connect with NPA and Tom House?: “I started following Tom House on Twitter, and he was putting stuff out there that was profound information. He was also articulating things opposite to what I was learning elsewhere. The only thing I knew about Tom was that he was Tom Brady’s throwing coach. I saw Brady’s documentary, ‘Tom vs. Time,’ on Facebook Watch in 2018. Tom Brady is my idol, and Tom was fixing him. If I could work with Brady’s guy, he could fix me too.

I was doing a ‘Punch Out Pitching’ podcast in addition to my Instagram. To get Tom to be a guest on my podcast, I lied through my teeth about the number of people downloading the program. I planned to get my biomechanics on Zoom for him to look at before I interviewed him for the podcast.

Tom told me so many things that would fix me, and it was stuff that nobody had told me before. He made it seem I could make these changes and gain six miles per hour—three real and three perceived. I was ready to run through a brick wall. I asked him if I could send him some videos when I started working on these adjustments, and he said yes. I started hammering his video account. Jordan Kutzer, one of Tom’s former pitchers who played at Stanford, was a gatekeeper on Tom’s email. He saw enough improvement from me that he passed some videos along to Tom.

Mustard did a weekly mechanics call every Tuesday evening at six. Jordan gave me the link and said Tom would evaluate my video. I cleared my schedule of lessons and worked with Tom as he broke down my video every week, giving me new things to work on or fix. I did this every week for four straight months.

I was getting better, throwing harder, and my fastball was straighter. My mom, grandmother, and the entire family were often downstairs trying to listen to these calls. I told them I desperately wanted to go to California to train with Tom, to be in person and see what happened.

I then sent him a video of me throwing a four-ounce ball ninety-eight miles per hour. That’s when he called and gave me three days’ notice with an invitation to attend a National Pitching Association camp in San Diego. He said he wanted me to come out to see if I was for real. I flew out on a one-way ticket because I thought my career was about over, but I wasn’t telling anyone I felt that way. I was so scared to say to people that, oh shit, this may not work. I had one chance to work with THE Tom House at this camp. I backed myself into a corner, telling myself I wasn’t coming home without a contract.

My grandmother, Donna Courtney, bought the flight for me. It was five hundred bucks one way. I told her I had the money for it, but Nana said she saw how much I enjoyed the weekly calls with Tom and to have fun. She told me getting home was up to me, but to enjoy the weekend. I told myself I’d be a failure if I returned to Maine without a professional contract. I went to the camp, and Tom asked me to stay for a few extra days to get me in front of some scouts. I wasn’t going anywhere and slept on the couch of someone I’d just met at camp.

How did you get signed by the Angels?: “The camp was on Friday, Saturday, and Sunday. On Sunday, I run-and-gunned 101 miles per hour with a four-ounce ball and threw 96 to a catcher with a four-ounce on flat ground. On Tuesday, Tom gave me the number of someone at the Padres, and they told me they would watch me throw. When Tom called me, the press conference for Padres’ general manager A.J. Preller’s contract extension was on television. The number he gave me was Preller’s. I was like, ‘What?!?! You are giving me Preller’s number, and he will watch me throw tomorrow? Tom gave me the wrong number. I called back and said, ‘Tom, you gave me the wrong number.’ Tom said, ‘Darn, I can’t even read my own writing.’ I called, and A.J. picked up the phone.

A.J. and Pete DeYoung, the Padres pro scouting director, watched me throw at Mission Bay Little League. This field wasn’t well-manicured, to say the least. The evaluators stood behind my catcher, with a radar gun and no fence. A.J. stood just outside the righthanded batter’s box watching pitches go by, and the pro scouting director was just off center with his radar gun right behind the catcher doing the same thing. I was shaking. Danny Camarena, a Padres player, and my soon-to-be battle buddy was also there because he was getting ready to throw a bullpen before leaving for major league camp. Tom was going to run the workout, but Tom Brady called and asked him to work out something on Zoom before the Buccaneers played in the Super Bowl against the Chiefs. I wasn’t surprised that Tom Brady took precedence over little ol’ me.

The workout came and went. Toward the end, A.J. rolled me a baseball up the third baseline to see how well I moved. Daniel acted as the first baseman, and I threw it ten feet over his head and down the rightfield line on the first throw. My shaking still hadn’t stopped. The rest of the throws to first were okay. I talked to the Padres players and scouts after the workout. They liked my frame and said I had a great body but wanted my curveball to have more bite, and they wanted to see a bit more velocity on my fastball. They asked if it was a regular bullpen because I was throwing 91 to 93. I said it was, and I’d just maxed out at the NPA. camp on Sunday with the four-ounce ball. They told me they’d be in touch.

We left the bullpen session, and Danny drove me to Fitness Quest 10 to train with Todd Durkin, trainer for Danny and Drew Brees. Danny asked me if I had worked out or lifted since I had been in San Diego, which I still needed to do. I called Tom on the way and told him what happened in front of the Padres’ brass and that they didn’t seem interested. He told me not to worry. He had a few other interested teams and would make some calls. I was in an Uber leaving Fitness Quest when a Toronto number rang on my phone. I immediately thought it was someone from the Blue Jays, but instead, it was David Haynes, the Director of Player Procurement for the Los Angeles Angels. He had heard about my workout with the Padres, and they wanted to offer me a contract with the Angels and a $5,000 signing bonus. He asked me how that sounded. I said, “Deal!” It was only five hours after the Padres’ watched me pitch and one week after arriving at Tom’s camp. I had a contract with the Angels.”

What was your experience like with the Angels?: “I expected everyone at the professional level to be better than my college coaches, trainers, and strength coaches, which was only the case in some areas with the Angels. I thought all the players would throw absolute fuel, but that wasn’t always true. Some did, some didn’t. I was expecting everyone to be super polished, but when I showed up at spring training, everyone was all over the place trying to figure things out. Some players were less confident than I thought they’d be. I thought they already had things figured out regarding analytics, but the Angels were guessing on some things and didn’t necessarily know what they were doing in every area, which I’m sure is the case for almost every team.”

Heading into 2022, it was the first offseason I had been healthy in a long time. We focused that offseason on making sure my body and arm could handle the demands of being a relief pitcher for an entire season and maintaining my stuff through a full season. We spent a lot of time on recovery and getting my body in better shape to bounce back quicker. My first season with the Angels was the first time I’d ever been in the bullpen, and I had to pitch multiple times every week. My arm wasn’t in as good a shape as it could have been, and I wasn’t in as good a shape total body-wise as I needed to be. We got to work on balancing off my shoulders–both accelerators and decelerators–with both throws and holds. It was a big piece of that winter. When I went to spring training at the end of that offseason, I tried to make an impression however I could. We had adjusted my delivery a little bit.

justin as the young nolan ryan in "facing nolan"

I was kicking my leg higher after working on playing a young Nolan Ryan in the ‘Facing Nolan’ documentary. It was right after I shot the movie. I shot the movie and figured out that if I had a higher leg kick in the same timing, the ball came out a little faster. During that spring training, I hit 95 for the first time. I went to Brooklyn and started the year really well. I had ten days when I uncharacteristically couldn’t throw a strike and was getting hit. I don’t know if I was trying to throw too hard and getting caught up in the radar gun or getting caught up in the game that the Mets wanted me to play with some metrics and percentages that they wanted me to hit rather than pitching my game. I went back to what we did in the offseason that year: not even try throwing until my front foot landed. My timing was off during those ten days. I then went on a tear and didn’t give up an earned run for nearly two months. Shortly after that, I got promoted to Double-A, which had been my goal for that season. I performed well there at the end of the season.”

You were a non-roster invitee to the Mets’ MLB camp the following year. How did that experience help you grow?: “Last offseason, we worked on developing more of a swing and miss breaking ball and having the ability to throw my breaking balls for strikes more often by tightening up my front side, and we tightened up my arm path, so I had less moving part on my upper body. When I threw breaking balls or off-speed pitches for strikes early in the count, hitters were much less effective against me. At spring training, I was a part of MLB spring training games. I was a just-in-case guy and was available whenever the Mets needed me. It prepared me to be in the bullpen for every big league game that spring. I traveled with the team and performed pretty well in those games. The Mets still wanted me to increase my velocity. I was overthinking about some of the mechanical adjustments I had made instead of going out and just letting it eat. But, ultimately, that spring training experience and being around major league guys like (Max) Scherzer, (Justin) Verlander, and Edwin Diaz for those games was really helpful. Brooks Raley was my favorite guy when he was there. He was always available to talk. He’s awesome. He went to Korea and returned to the majors, so he has a great story. Being around those big leaguers last spring helped me realize I am good enough to compete at that level. I knew I could get any hitter out at any time.”

What have you been working on this offseason?: “During last season, I was doing some heavy ball holds almost every day, and I wasn’t working on speed hardly ever throughout the season. I learned in 2023 that I was comfortable with my bullpen routine, whether getting warmed up quickly or getting up and sitting back down for two innings and then getting ready again. I knew what it took to get prepared. I wasn’t enough to keep the speed up. I should have known. I had to explain to the Mets why I was doing some of the protocols I was doing. I told them my arm felt better when I held the heavy balls instead of throwing them, and as soon as I told them why, they were good with it. I was always healthy and always ready to go.”

What has the NPA family meant to you?: “I know that whenever I’m working with someone associated with the NPA, as a coach or player, you know you are working with a first-class human being. You’ll be working with someone you can trust and will do whatever they can to help you in every way. So many scenarios come up when you may be traveling to a strange place or need a place to throw, and there’s an NPA guy there to help. You instantly bond with people that way. It really is like a second family in that sense. Coaches treat you like their own son, and they are looking out for your best interest. Because I always know they are giving their very best, I give my very best. Both parties walk away better from the experience. You don’t get to work with the NPA as a coach if you are a bad person. If they can’t help you themselves, they’ll look for someone who can help.”.

What makes Tom House unique?: “Tom is the only coach I’ve worked with who looks at you through a baseball and personal lens. He’ll look at any player through multiple lenses. He sees me as a righthanded reliever who can be a setup guy for a first-division team. He looks at someone whose family means a lot to him through a human lens. He looks at you as a person and takes everything into account. He looks at your personality to see how he can best instruct you. He wants to develop a complete pitcher by looking at who you are. He’s the only coach who views me as a human who plays baseball and not a baseball player who is a human. Some so many coaches have their identity wrapped up in being a baseball coach. The first time I met Tom, I met him for breakfast. I expected him to pull up in a Benz, and he pulled up in a VW Bug. That’s Tom.”